As the percentage of Covid infected among us continues to drop, I have started to re-engage the outside world. A couple of weeks ago, I was worried that I was beginning to become an agoraphiac, as I had not driven my babies in quite some time. I wrote about it and received a nice rasher of shit from my Flat Six (AKA Porsche) cronies, telling me in no uncertain terms to get out and drive. And so I did.

Last weekend I met my friend Mark at the gas station, and then we went for a drive. It was pleasant. Nothing serious. Nothing twisty. Nothing fast. Just a nice drive up the coast. I was in my Cayman, and he was in his 911. Both of us were on our phones with each other, as being the yentas we are, we kibitzed as we drove. We did about 90 miles up and down the coast with a nice stop north of Malibu at Trancas for some coffee and muffins. It was great. It was just what the doctor, if not Eric Garcetti and Barbara Ferrer, ordered. It left me feeling less agoraphobic.

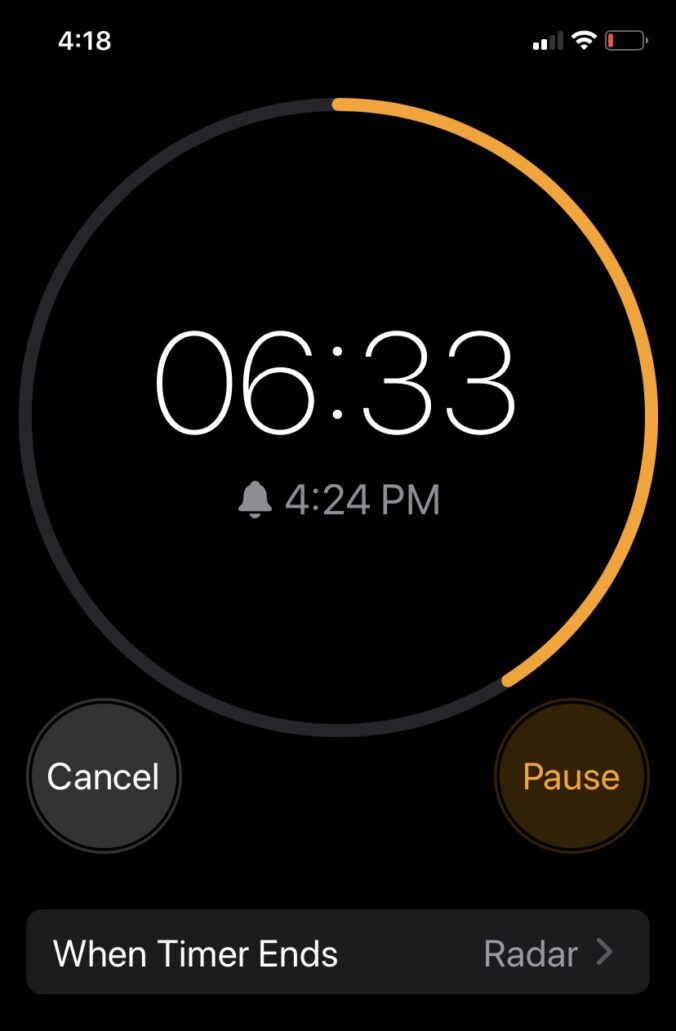

This weekend I decided to do it again. Only this time I went alone, and I drove my 89 Carrera, mainly because I wanted a more visceral experience. We are suffering through a fall Santa Ana wind condition, with daytime temperatures in the 90s and 100s. No matter, as I headed out early Saturday morning with the Targa top off and the hot, Santa Ana winds whipping through the cabin.

I was still not in the mood for a serious drive, so I did most of the same one Mark and I did last weekend, only this time I was not on the phone. Instead, I was focused on the drive, remembering what driver engagement is all about when driving a fully analog car without nannies like traction control, without power assisted anything, and without the dual-clutch automatic transmission that lurks in my Cayman. In short, my focus was on the tachometer, as I shifted my way up and down thru the gears, listening to the sound of the air-cooled flat six as it competed with the wind for my attention. There was not much else on my mind. At least initially.

At some point, driving became automatic. The wind and the engine sound became consistent background noise that soothed me but enabled me to start focusing on other things. Like the conversation I had had with my friend Nick earlier in the week.

Nick is a really smart guy. He is a young entrepreneur driven to be a success. He is also one of the most knowledgeable people I know with respect to world and economic events. We see eye to eye on almost every issue we face as Americans.

Given that we agree on so much, why do we continue to discuss the issues? The answer is simple: We are voting for different presidential candidates. So we discuss the issues to try to find the nuances that lead each of us to our distinctly different choice.

After much thought, I realized that it is not only the individual issues that drive our decisions. Instead, it is our prioritization of each of the issues and the implication of the solution to each issue that leads us to different conclusions, because ultimately it is what each of us fears the most that matters more than what we agree upon. That is why we keep discussing the issues.

The drive back was a blur, as I ruminated about Nick and life in America in 2020. Soon I was nearing the end of the drive on the coast, approaching the McClure Tunnel and the start of Interstate 10 eastbound.

It was time to shift my focus back to driving, but before I did, I though about Nick and our relationship. Nick and I respect each other. We value each other’s opinion and thoughts. We see value in our friendship despite differing political views. We will still have a relationship after all the votes are counted, whichever month that is.

I hope the same can be said for the majority of Americans.